Focusing on the keyphrase “Stone Age megastructure discovery,” the article discusses findings related to ancient structures from the Stone Age.

Discovery of Stone Age Megastructure

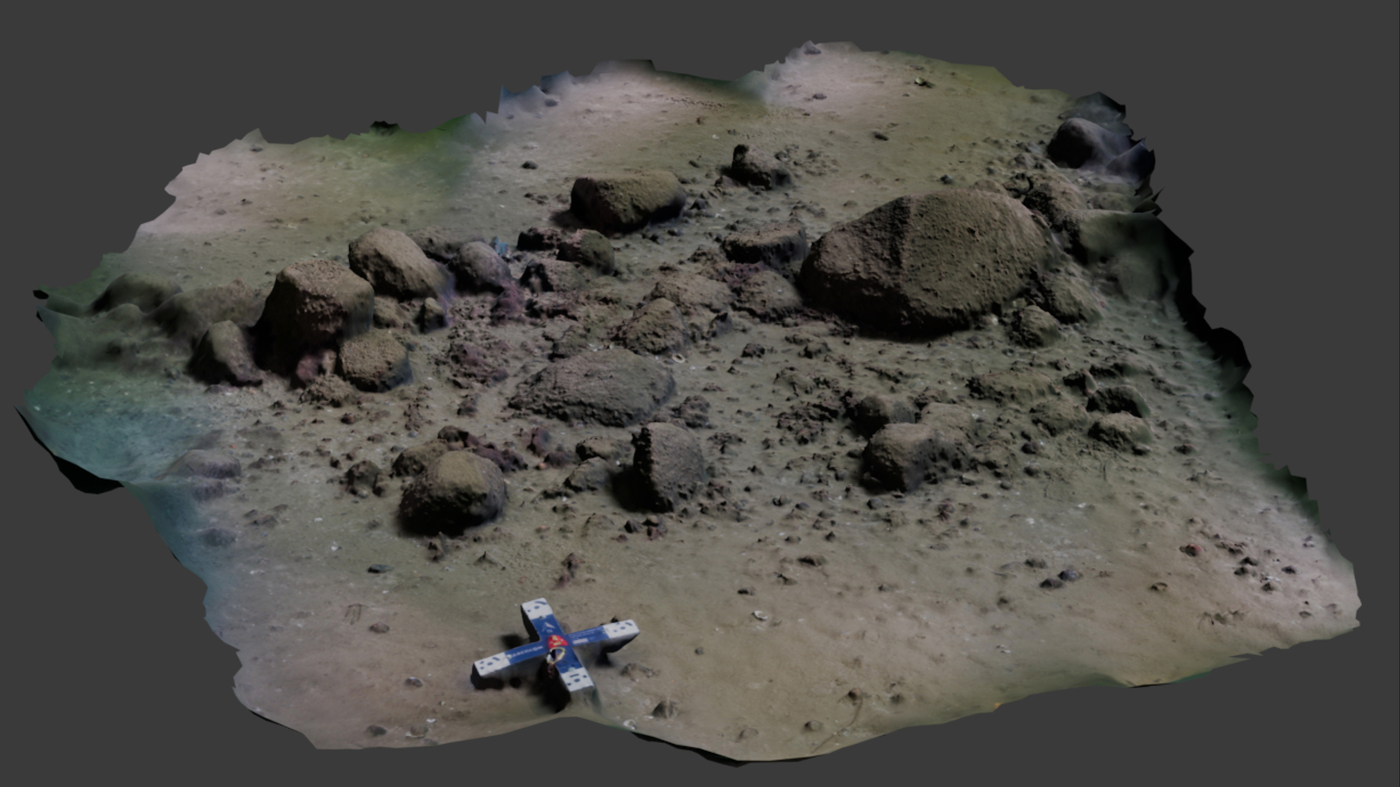

A 3D representation of a segment of the stone wall is depicted in the image, with a scale indicating 50 cm at the bottom. The credit for the photos goes to Philipp Hoy from the University of Rostock, and the model was crafted using Agisoft Metashape by J. Auer from LAKD M-V.

In autumn 2021, Jacob Geersen, a marine geologist currently affiliated with the Leibniz Institute for Baltic Sea Research, led a week-long field course at the University of Kiel. The course took place entirely on a research vessel navigating the Baltic Sea.

Geersen favors the outdoor classroom setting, describing it as intense but possibly the most memorable time for some students during their academic journey.

Each night shift, students meticulously charted the contours of the seafloor with great detail. Geersen noted that such expeditions often lead to intriguing discoveries. This particular research voyage was no different.

During an evening in the Bay of Mecklenburg, situated along the northern German coast, students activated the echosounders and surveyed a section of the seafloor. The following day, upon reviewing the collected data, Geersen and the students were astonished to find a significant feature on the seafloor.

Unbeknownst to them initially, approximately 70 feet beneath the water’s surface, they had encountered a stone wall stretching over half a mile, dating back to the Stone Age. This ancient megastructure, detailed in a publication in PNAS by Geersen and his team, is believed to have served as a hunting structure for corralling and hunting reindeer, showcasing the advanced skills of the prehistoric hunter-gatherers from 10,000 to 11,000 years ago.

Unveiling the Stone Age Megastructure: The Blinkerwall

Geersen had grown accustomed to identifying rocks and stones on the echosounder, appearing as irregularities scattered on the Baltic Sea floor, remnants of the ancient glaciers’ retreat from northern Europe. However, aboard the vessel in the Bay of Mecklenburg, he immediately noticed a distinct difference in what he was observing.

“There was a feature that seemed to snake through the map,” Geersen recalls. Stretching for six tenths of a mile, he suspected that these were rocks aligned side by side.

A year later, Geersen, along with his team and a fresh group of students, revisited the same location. They deployed a camera, confirming that the ridge consisted of thousands of rocks forming a wall standing at an average height of 1.5 feet.

“The stones are typically small, resembling tennis or soccer balls – easily movable,” explains Geersen. “However, in certain areas where larger stones are present, the wall’s direction shifts.”

Perplexed by the origin of this structure, which they named the “Blinkerwall” in reference to a nearby underwater elevation known as Blinker Hill, Geersen and his team were puzzled by its natural formation.

Unearthing a Remarkable Stone Age Megastructure

Upon consulting with archaeologists, the team received validation of the potential significance of their discovery. Berit Eriksen, a prehistoric archaeologist at the University of Kiel, initially harbored skepticism but was intrigued by the findings. Eriksen, specializing in the study of early inhabitants in northern Europe post the Ice Age, found herself reminded of a Sherlock Holmes quote when examining the structure from the Bay of Mecklenburg: “When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.”

While acknowledging that archaeologists refrain from definitive claims of ‘truth,’ Eriksen expressed her challenge in ruling out natural explanations. After a thorough review of the data, she became increasingly convinced that the structure was crafted by prehistoric humans. By meticulously assembling smaller stones to interlock the larger immovable rocks, Eriksen deduced the manmade origin of the structure. The consensus among the archaeologists involved in the project was that the wall likely served as a tool for hunter-gatherers during the Stone Age, aiding them in herding and hunting reindeer thousands of years ago.

Uncovering the Strategy of Hunting Reindeer in the Stone Age

“To successfully hunt a large number of reindeer in the Stone Age, one had to lead them towards a shooting blind or block their path,” Eriksen explains. Reindeer naturally tend to follow stone walls like the impressive Blinkerwall.

Eriksen points out, “There was likely water on the other side of the wall.” This setup would have trapped the reindeer between the wall and the water, making it easier for the hunters hidden in ambush to shoot their arrows. The presence of such a wall indicates that these ancient people, although nomadic, possibly had a regular migration route that led them back to this location annually.

Uncovering a Stone Age Megastructure Discovery

“When constructing a structure like this,” Eriksen explains, “it showcases a deep understanding of the entire region. It’s not merely navigating through unfamiliar terrain. There’s strategic planning involved. Anticipating where the reindeer will be next year is key.” This concept has been a topic of discussion among archaeologists, and the recently discovered wall adds weight to the theory that it was indeed practiced in prehistoric Europe.

Over time, the region was engulfed by water, giving rise to the Baltic Sea as we recognize it today, submerging this remarkable piece of hunting architecture beneath its waters.

Ashley Lemke, an underwater archaeologist at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, commended the study, emphasizing the rigorous work carried out under demanding conditions.

“Having firsthand experience, I can attest that underwater exploration is no easy feat,” says Lemke, who has uncovered similar stone structures in Lake Huron, one of the Great Lakes adjacent to Michigan.

Lemke highlights that these findings challenge the common perception of Stone Age inhabitants as mere survivalists. “There’s a misconception that they were constantly on the brink of starvation, struggling to eke out a living. The reality is quite different,” she asserts. “Communities in Europe were engaging in architectural endeavors predating Stonehenge and other iconic structures.”

“These early examples hint at a form of proto-animal domestication,” Lemke elaborates. “Before the era of permanent animal pens, people were constructing barriers for hunting purposes, a fascinating precursor to livestock husbandry.”

To validate the hypothesis that the wall was crafted by prehistoric individuals for hunting, further archaeological evidence of hunting-related activities is required. Berit Eriksen suggests that such evidence should exist, given that hunters would have spent time waiting for the reindeer.

“During their stay, they would have needed to eat, leaving behind traces like small charcoal remnants,” she explains. Excavations may reveal arrowheads or ancient DNA. Additionally, Eriksen notes, “They would have also left waste behind, offering potential insights into their presence if we’re fortunate.”

Please visit our site 60time.com and please don’t forget to follow us on social media at Instagram.