Using the keyphrase “Ghana resettlement plans resentment,” the article delves into the challenges faced in Ghana regarding resettlement plans.

Ghana Resettlement Plans Resentment

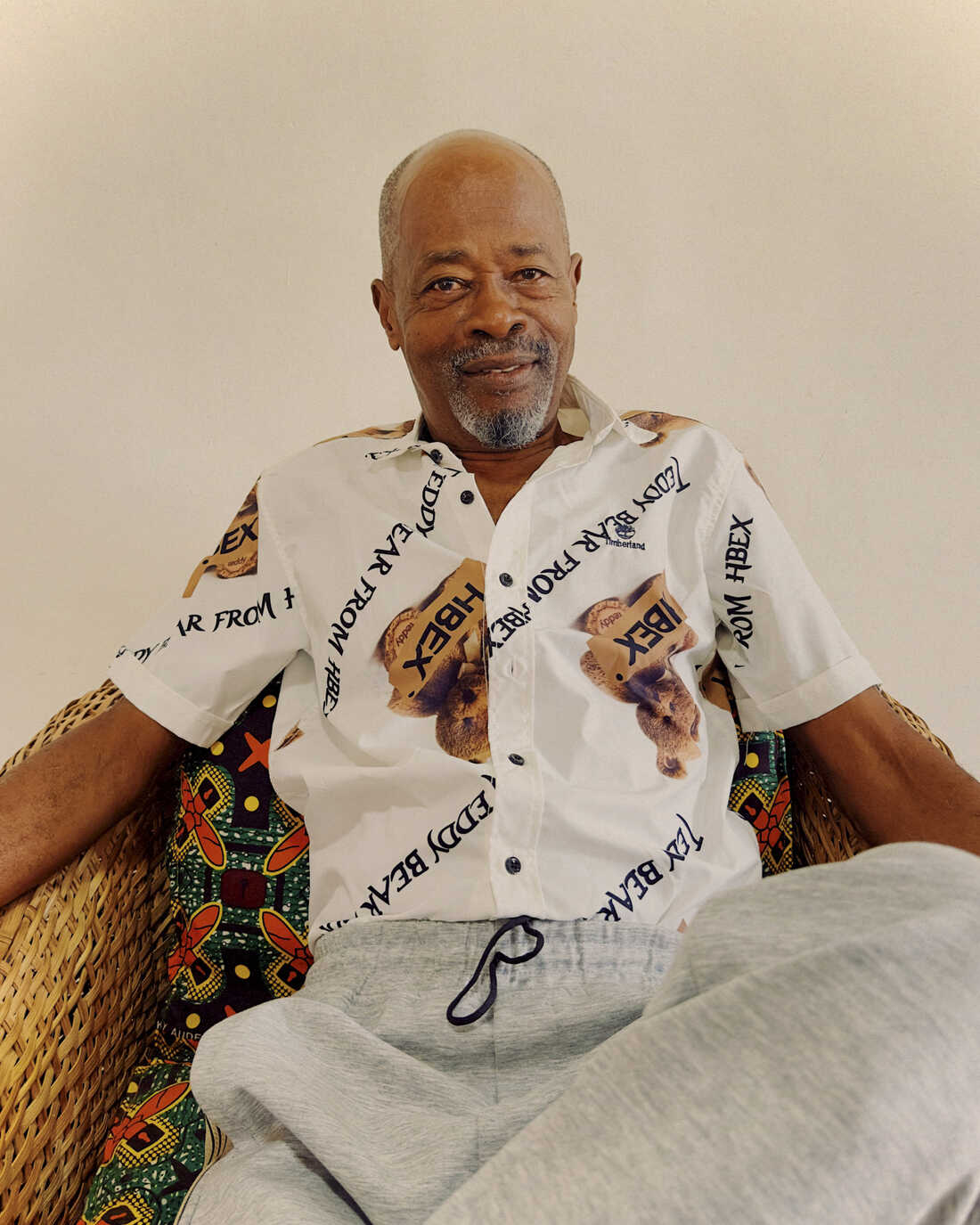

74-year-old Lenval Skiers is situated at his residence in Pan-African Village, located in Asebu.

Jude Lartey for NPR

74-year-old Lenval Skiers at his home in Pan-African Village, in Asebu.

ASEBU, Ghana — A tranquil 5,000-acre rural settlement rests in the quiet town of Asebu, a short distance from the Atlantic along Ghana’s Cape Coast. The entrance features a mud road that winds through a lush green landscape dotted with numerous homes and partially constructed concrete buildings, surrounded by vast farmland and palm trees.

“Nobody has inhabited this area before,” mentions Lenval Skiers, a 74-year-old resident, from the sunlit lounge of his six-bedroom home and guesthouse. “It was just me in the forest. The land was unutilized, but I took the leap.” Skiers, from his expansive balcony on the second floor, gestures towards his extensive garden, abundant with cassava, avocado, and sugar cane clusters. Adjacent lies Pan-African Village, a piece of land transformed into an ideal sanctuary for settlers from the African diaspora.

Skiers is part of a small yet expanding community of around 30 individuals, mostly hailing from the United States, Canada, and the Caribbean. They consider themselves pioneers among a fresh African community in Asebu, crafting a new existence in their ancestral homeland, free from the racism and oppression experienced in the nations their forefathers were forcibly taken to.

They form part of a longstanding tradition, where numerous individuals of African descent have chosen Ghana as their home — a legacy championed by independence leader Kwame Nkrumah, envisioning Ghana as a symbol of African unity. Many are attracted to Ghana, portrayed abroad as a thriving African nation on the ascent. However, the influx of returning diaspora, though embraced, has become contentious during challenging economic times.

Within Pan-African Village, simmering tensions regarding land ownership and exclusive land access jeopardize its potential. “I was the initial settler here,” Skiers proudly states. “And more are following in my footsteps.” Although born in Jamaica, Skiers spent the majority of his life in Canada, working in a shipping factory for nearly forty years. However, Canada never felt like home to him. “Canada was constructed by white individuals. We, as Black and Indigenous people, were viewed as second-class citizens.” Upon retirement, he was determined to leave and envisaged a new life elsewhere.

A road leading to the village.

Jude Lartey for NPR

A road leading to the village.

In 2020, the traditional ruler of Asebu Town, the “paramount chief” of the region, presented a unique opportunity. He declared the allocation of 5,000 acres of farmland in his town, offering free plots to individuals of African heritage in the diaspora planning to settle there.

Through social media platforms, notably YouTube, influential figures endorsed the settlement as a rare chance to acquire valuable land in Ghana, a nation depicted as a prospering African state. Skiers engaged with several such videos and contacted one influencer, Ekow Simpson, who encouraged him to embark on the journey. “I saw the vast land and believed I could secure a piece of it,” Skiers expresses.

The settlement was granted as part of Ghana’s 2019 Year of Return, a government initiative urging individuals of African descent to “return” to Ghana. It marked a significant historical moment, occurring 400 years after the initial ships transported enslaved Africans from West African ports across the Atlantic to Virginia in the United States. Since then, thousands have relocated, settling in Ghana, with over 560 individuals acquiring land, paying administrative fees ranging from $1,000 to $1,200 per plot to the paramount chief.

“We’ve reached a point where there’s an option to depart from these nations,” Skiers remarks, “to find land in countries where you can experience complete freedom. Freedom from racism, freedom from unemployment, and low wages.”

Nevertheless, the settlement has instigated resentment within the local community, despite the burgeoning construction and economic activity it has stimulated in Asebu — a breezy, bustling town primarily inhabited by lower-income farmers, construction laborers, and tourism-dependent businesses. It has sparked vehement opposition that risks escalating into violence and raised concerns about whether Pan-African Village, parts of which belonged to various local families, should have been relinquished.

Impact of Ghana Resettlement Plans Resentment

Reflecting on the situation, 59-year-old farmer Kwesi Otu-Bensil expresses his dismay, “We’ve cultivated that land for generations. Now, it lies in ruins.” Gathered outside his simple home in Asebu, Otu-Bensil, along with a group of farmers and his extended family, the Akoa Anona’s, are surrounded by small vegetable plots and roosters.

Otu-Bensil previously tended to yams, coconuts, oranges, and various other crops on 123 acres of his family’s land, now incorporated into the Pan-African Village. However, in 2020, the paramount chief claimed ownership, leading to the flattening of the fields. This act of destruction and dispossession has severely impacted Otu-Bensil and more than 150 farmers who depended on the land for their livelihoods. “Previously, if I made 100 cedis [$8.33], now I struggle to earn 30,” he laments, highlighting the challenges of supporting his family of five children.

Abusuapanin Kojo Badu, aged 68 and Otu-Bensil’s cousin, holds a significant position within the family. Displaying a map of the land and the registration certifying his family’s land ownership, recorded in Ghana’s land registry, Badu emphasizes their rightful claim to the land. Upon learning about the paramount chief’s intentions for a diaspora settlement in Asebu during the Year of Return, Badu acknowledged the concept but asserted, “The land belongs to my family.”

Ghana Resettlement Plans Resentment: Asebu Farmers’ Struggle

Asebu farmers are embroiled in a dispute over their family land, which they claim was unjustly taken by the paramount chief and incorporated into the Pan-African Village. The farmers, including Samuel Kumi, Kwesi Otu-Bensil, and Daniel Kweku, have been vocal about their grievances.

Jude Lartey for NPR

The Paramount Chief’s Refusal to Compensate

Kojo Badu, a member of the affected family, recounts how the paramount chief adamantly refused to compensate them for the land. Despite numerous discussions, the chief insisted on not paying, claiming it would be provided for free. Badu stood firm, rejecting the notion of giving away their land without compensation.

As negotiations reached an impasse, the paramount chief asserted his legal authority over the land and seized it without offering any form of compensation to the 150 farmers affected. Tragically, Kojo Badu reveals that five of his relatives, including two siblings, passed away in the past two years due to exacerbated illnesses resulting from the loss of their livelihoods.

Legal Battle and Unresolved Construction

In response to the land seizure, the family took legal action against the paramount chief and other parties involved in the Pan-African Village project. Despite a high court injunction issued in October 2023, halting construction on the disputed 123-acre land claimed by the Akoa Anona family, construction activities continued unabated, disregarding the court order.

Daniel Kweku, a 44-year-old farmer from the family, expressed outrage upon discovering ongoing construction on their land in defiance of the court injunction. Confrontations ensued, leading to Kweku and two family members being unjustly arrested by the police. Although released without charges after three days, tensions escalated further.

Threats and Intimidation

Kweku’s attempt to reclaim his family’s land was met with threats of violence, deterring him from proceeding. Reports of diasporas in Pan-African Village possessing firearms raised concerns among the Akoa Anona family and other Asebu residents. The proliferation of guns in the once-peaceful community has sparked fear and resentment.

The presence of armed security guards and residents wielding firearms has intensified the conflict, exacerbating the already strained relations between the affected farmers and the newcomers in Pan-African Village. The prolonged legal battle over the disputed land has only added to the mounting frustration among the aggrieved parties, as resolution remains elusive.

Exploring Ghana Resettlement Plans and Resentment

In the past, the land lay untouched, devoid of any inhabitants. The grand residence of the paramount chief of Asebu stands proudly atop a hill, offering a commanding view of the town. Amanfi VII, the esteemed leader of Asebu, expresses his desire to demonstrate care for the diaspora community. “Our brothers and sisters from afar should know that we hold them in high regard,” he shares from his office. “Being of African descent, they have every right to claim a piece of our land.”

Over the years, numerous international visitors, particularly from the United States, have been captivated by the historical slave ports scattered across Cape Coast, serving as poignant reminders of the trans-Atlantic slave trade atrocities. Amanfi VII acknowledges the dilemma of enticing these visitors to prolong their stay. He emphasizes the importance of providing lasting experiences to prevent a fleeting visit characterized by momentary sorrow at the castles, followed by a swift return to the U.S. This challenge led to the creation of the Pan-African Village, a visionary initiative supported by Ghana’s president, Nana Akufo Addo.

Ghana Resettlement Plans Resentment

A photograph showcasing the Cape Coast Castle, with image credit attributed to Jude Lartey for NPR.

The paramount chief asserts his legal ownership of the land, referring to it as “stool land” under his jurisdiction. He maintains that no individuals were displaced from the area, emphasizing that it was previously uninhabited. Only a small number of individuals engaged in farming activities on the land and were duly compensated.

The Pan African Village represents one of the increasing diaspora settlements in Ghana, particularly following the Year of Return initiative. Another notable settlement, previously known as Wakanda One City, inspired by the fictional realm in the Marvel comic and film Black Panther, is also in the works in Cape Coast.

However, some settlements established decades ago serve as cautionary tales. Fihankra, a 200-acre community established in Ghana’s eastern region by a group of African Americans in the mid-90s, aimed to provide a safe haven for returning diasporas. Tragically, the development turned violent due to a land ownership dispute between locals and the diaspora, resulting in the tragic murder of two African-American women in 2015. Subsequently, a local man was convicted and sentenced to death.

Embracing Ghana Resettlement Plans Amidst Resentment

Sixty-nine-year-old Hoyen Vivalee, a neighbor of Lenval Skiers, made her way from Atlanta, Georgia, to the village in 2022. Her vibrant two-story lime-green and orange residence, featuring guest quarters for visitors, stands out like a charming dollhouse in the community. Despite the ongoing land dispute among farmers in Asebu, her aspirations for a fresh start in Pan-African Village remain unwavering.

Seated at the far end of her white living room, Hoyen Vivalee rests on a wooden throne with her feet propped up on a stool, atop a lion-print rug. Adorned in traditional Ghanaian kente fabric draped over her shoulder, she now goes by the name Na Bwafwoyena Oyem Mpese Tulu I, along with a new prestigious title. “I proudly hold the esteemed position of Diaspora Development Queen for the entirety of Ghana,” she proudly declares.

Ghana Resettlement Plans and Local Resentment

Na Bwafwoyena Oyem Mpese Tulu I, previously known as Hoyen Vivalee, was honored with a chieftaincy title by ethnic Ga chiefs, who appointed her as the “Diaspora development queen of Ghana” at the age of 69.

Tulu, who hails from Jamaica and spent most of her life in the U.S., found hope in Ghana after facing financial struggles in her retirement. In 2021, a friend invited her to visit Ghana, where she eventually settled in the Pan-African Village, finding relief from financial burdens.

She was crowned by Ga ethnic group chiefs to lead diaspora efforts in Ghana, aiming to uplift communities like Asebu by proposing innovative investment plans, such as building pay-to-use toilets to combat open defecation.

Despite her positive impact on the village’s development, Tulu faces challenges in fully integrating with the local community. She acknowledges the resentment felt by some locals, emphasizing the importance of hard work and investment in acquiring land in the area.

An Insight into Asebu Town

An overview of Asebu town reveals a blend of cultural richness and economic potential, with initiatives like Tulu’s diaspora development plans aiming to drive progress and prosperity in the region.

“Concerns Over Ghana Resettlement Plans Resentment”

Following the Year of Return initiative, Ghana has experienced a surge in visitors, with over 100,000 people traveling to the country in 2019, contributing nearly $2 billion to its economy. This influx has attracted individuals seeking a promising West African democracy on the rise, leading to a significant migration to Ghana.

Despite Ghana’s growing popularity as a gateway to Africa, contrasting perspectives on the country have emerged. While it is viewed favorably internationally, many locals perceive Ghana as facing a period of decline. Economic challenges, such as soaring inflation rates exceeding 35% and a devalued currency, have plunged the nation into a financial crisis, prompting a $3 billion bailout from the International Monetary Fund.

Land disputes and settlement issues have long been contentious topics in Ghana. While tensions have escalated in some areas like Pan-African Village, where conflicts have led to armed confrontations, other individuals have approached the situation differently. Nana Kofi, a 75-year-old who relocated to Ghana from St. Louis in 1997, shares his experience from the tranquil setting of a medical facility he established within his community, providing affordable healthcare services.

Ghana Resettlement Plans Resentment

Nana Kofi stands proudly outside the clinic he constructed alongside his daughter.

Jude Lartey for NPR

Nana Kofi outside the clinic he built with his daughter.

Jude Lartey for NPR

In 2010, he relocated to Elmina, near Cape Coast, and acquired land from a local family. Following the purchase, a faction within the family disputed that they were not adequately compensated and were forcibly removed from their land.

“It was chaotic!” Kofi remarks, mentioning that African diasporas who had settled there often found themselves entangled in land conflicts. “However, I opted to compensate them, as the sum they demanded held significant value for them, whereas for me, a few hundred dollars for land wasn’t as burdensome.”

In Asebu, concerns are mounting about the potential outcomes of the escalating tensions. Ato Wright, 44, a landowner and agent, is part of a burgeoning group of intermediaries aiding foreigners in purchasing land around Cape Coast.

“You cannot simply instruct me to vacate this land so you can gift it to your diaspora sibling for free. Such actions breed animosity,” Wright asserts. “Encouraging our African brethren to settle in Asebu was a commendable initiative. However, it is crucial for the locals to also feel a sense of inclusion. We should perceive that we have also reaped benefits.”

Farm owner Kwesi Otu Bensil, distressed by the expropriation of his ancestral land, portrays the African diasporas in Pan-African Village in conflicting and revealing manners. At times, he refers to them as “brothers and sisters,” while at other times, as “the whites” who have taken over his land without his consent.

“They have erected their residences, their bungalows. They have enclosed it,” Bensil laments. “Now, we are barred from accessing it. The fear of repercussions prevents us from venturing there.”

Please visit our site 60time.com, and don’t forget to follow us on social media at Facebook.